[Editor’s note: This is the ninth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

Mayan hieroglyphics form a complex and visually striking writing system. Meaning has to be interpreted from a combination of signs representing syllable sounds (syllabograms) and words (logograms). These glyphs were once considered an unsolvable enigma, but recent advances in decipherment have shed light on both the mechanics of the script and also the socio-political, artistic, and historical aspects of Mayan civilization.[1]

The Mayans created the longest-lasting civilization of the New World, beginning in the middle of the first millennium BCE, and adapting and changing over the centuries until they fell to the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Mayans as a people, though, have survived. Today there are at least one million Mayans living in Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.[2]

The Mayans were not actually a single people but were instead many nations with different, but related, cultures, religions, and languages (37 distinct dialects). Of those languages, only two – and possibly three – were written down using the hieroglyphic system. Scholars believe that speakers of the Ch’olan language, and perhaps also those of the Tzeltalan language, invented what we know as the Mayan writing system, while speakers of Yucatec later adopted the script to codify their own dialect. Some artifacts bear both languages in hieroglyphic inscriptions (a biscript); this offers tantalizing clues into how Mayan languages may have developed and interacted. The prevailing thought at this time is that Mayan writing grew out of an even more ancient writing system, one developed by the Olmecs as early as 1000 BCE.[2]

The earliest examples of Mayan writing date from the Late Pre-Classic period (300 BCE to 300 CE). Many of these early texts, though, were found on objects looted from their archaeological context – they therefore can’t be dated using radiocarbon dating or other common physical dating techniques. Instead, their ages were estimated based purely on a comparison of the artistic styles of the objects to archaeologically excavated artifacts.

This situation changed when archaeologists made major discoveries at the site of San Bartolo, which yielded beautifully painted murals as well as some of the earliest Mayan texts found in their archaeological context. The texts associated with the murals date to about 100 BCE; another piece of text, found in a different part of the city, dates to 300 BCE. This makes the find the oldest accurately dated Mayan text and one of the earliest known in Mesoamerica as a whole. However, the San Bartolo texts differ considerably from Mayan glyphs dating after 250 CE. It’s evident the two writing systems come from a similar source, but many of the signs look different enough that even experienced scholars can’t translate them with certainty.

Our ability to decode later Mayan writings began with Bishop Diego de Landa, a Spaniard who committed himself to destroying every Mayan book he could find. His system backfired spectacularly. While writing Relación de las cosas de Yucatán, he made the assumption that the Mayans wrote with an alphabet, like the Spanish. He inquired among the natives as to how they wrote “a,” “b,” “c,” and so forth, in Mayan. The Mayans, though, heard the syllables “ah,” “beh,” “seh” (as the letters would be pronounced in Spanish), etc., and so they provided the glyphs that represented them syllabically. In recording these along with the Spanish “equivalents,” Landa produced the Mayan version of the Rosetta Stone, paving the way for later scholars to be able to decipher the language.[1]

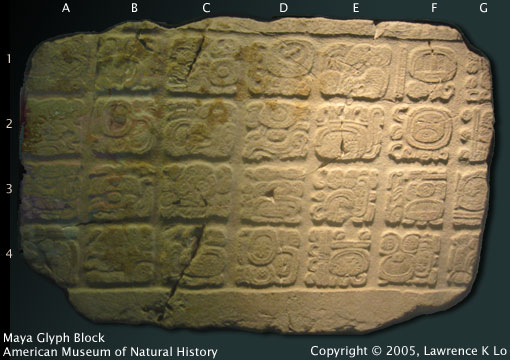

The visual construction of the glyphs is intriguing. At first glance, they appear to be very intricate squares laid out in a grid-like pattern. However, each square contains one to five glyphs and often forms a word or even a phrase. Because the blocks are in grids, you might believe they should be read in rows or columns, but neither is true. Instead, the glyphs are read in “paired columns” in a zig-zag order: the first glyph block is on the top left, the second is immediately to the right of the first, the third is under the first, the fourth is under the second, all the way down to the bottom. From the bottom of this paired column, you move back up to the top and start with the next pair.

There were several classes of glyphs in the Mayan writing system, but one of the most important was the numeric glyphs. Like us, the Mayans wrote their numbers in positional notation – the position of a “digit” dictates its numerical value. While we use horizontal positioning, the Mayans used a vertical one.

| 700 | = | 7 x 102 |

| 70 | = | 7 x 101 |

| 7 | = | 7 x 100 |

In this addition column, the Mayans used a dot to represent “one,” a bar to represent “five,” and a shell to represent “zero.” Instead of base 10, though, they used base 20.

Closely related to the numbering system is the Mayans’ intricate calendar system which involved several interlocking cycles, some of which tracked astronomical events while others followed seemingly abstract time intervals. As with other Mesoamerican cultures, the Maya used a 365-day solar calendar (jaab’) and a 260-day ritual cycle (tzolk’in). The jaab’ is divided into 18 “months” of 20 days, plus 5 “unlucky” days at the end called wayeb’.

Mayan jaab’ calendar symbols

Many historians have tried to decipher the Mayan script. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov was notable for realizing Landa’s alphabet was actually part of the Mayan syllabary; this led him to identify many of the syllabic glyphs. But perhaps the greatest advance was made by Tatiana Proskouriakoff, who noticed that stelas (monument or burial markers) come in groups and that many of the recorded dates didn’t seem to coincide with any religious or astronomical events. Instead, the dates fit with a person’s lifetime, leading her to conclude that at least some of Classic Mayan texts recorded information about rulers. From this observation, we have been able to piece together much of the ruling and social history of this once-great people.

Next up: The Aztecs and Nahuatl

Citations:

[1] Lo, Lawrence. (nd.) “Maya.” AncientScripts.com. Retrieved from http://www.ancientscripts.com/maya.html

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

3 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 8: Mayan Writing”