[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

“Philip K. Dick has been given many labels over the years and as his work has become more known since his death. He used the science fiction genre as an outlet to break unfamiliar ground. His work is very experimental and questions the basis of our own existence, and his own emotional and psychological states play a major role in the tone of his work throughout the years. Noticing the change in Dick’s writing style from the 50s to the 80s is a look at the struggles of a creative genius. His attempts to demonstrate the ever-expanding potential of the universe are personal journeys into his own realities.”[1]

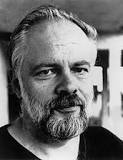

Philip Kindred Dick and his twin sister, Jane, were born six weeks prematurely on December 16, 1928, in Chicago. Jane died six weeks later, an event that profoundly affected Philip’s life and led to the “phantom twin” concept he often used in his stories. The family moved to the San Francisco area, but when Philip’s father was transferred to Reno, his mother refused to go, and the couple divorced. During his elementary school years, it’s interesting to note that Philip received a “C” in Written Composition; his teacher noted, though, that he “shows interest and ability in story telling.”

Dick briefly attended the University of California, Berkeley in 1949, but he didn’t declare a major. Instead, he took classes in a wide variety of areas including history, psychology, philosophy, and zoology. In an interview, he commented that his philosophy courses led him to believe that “existence is based on internal human perception, which does not necessarily correspond to external reality.” He also concluded that the world isn’t entirely real and there’s no way to prove whether or not it actually exists. The tenuous nature of reality and the revelation that all is not as it seems were ideas that flowed through many of Dick’s stories.[2]

Dick’s protagonists were usually drawn from the working class, not the elite. Science fiction great Ursula K. Le Guin astutely observed that “There are no heroes in Dick’s books, but there are heroics. One is reminded of Dickens: what counts is the honesty, constancy, kindness and patience of ordinary people.”

Dick’s first experience with the relatively new science fiction genre came in 1940, when he was 12. He was at a newsstand looking for a copy of Popular Science, but he picked up Stirring Science Stories instead. “I was most amazed,” he is quoted as saying on his official website. “Stories about science? At once I recognized the magic which I had found, in earlier times, in the Oz books—this magic now coupled not with magic wands but with science …. In any case my view became magic equals science … and science (of the future) equals magic.”

He began submitting his own short stories to science fiction magazines but made no progress at first, once receiving 17 rejection slips in a single day. But, in 1951, the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction picked up a story called “Roog,” and that seemed to open the floodgates. By the time it appeared in print, seven more of his stories had already been published. In 1954 he met the well-established SF writer A.E. Van Vogt at a convention, and Van Vogt told him that despite the notoriously low pay rates of science fiction publishers, novels would be much more lucrative than short stories. Dick followed the advice, and his first novel, Solar Lottery, was published in 1955.

Science fiction really didn’t pay well, and by the late 1950s Dick was so broke, he commented that he couldn’t even afford to pay library fines. His solution was to work relentlessly, and he used methamphetamines to boost his productivity, writing almost everything while high. Between 1959 and 1964 he published 16 novels, plus a number of non–science fiction works. Although he defended science fiction as a valid art form, Dick hoped his other books would pave the path to literary respectability. However, his agent returned all the manuscripts to him as unpublishable – only Confessions of a Crap Artist was published during his lifetime. He re-applied himself to science fiction.

Dick’s big breakthrough came in 1962 with the novel The Man in the High Castle, which won him the Hugo Award for Best Novel. He used his characteristic theme of alternate realities, but he placed them in a relatively conventional setting: the novel imagined a United States that had lost World War II and extrapolated the new timeline. This time, Dick relied on several years’ worth of historical research to add detail, and it won him praise from mainstream critics as well as the science fiction community. Dick’s 1964 novel Martian Time–Slip, one of four novels he published during that year, was also especially successful. The story featured a character who Dick described as an “ex–schizophrenic,” and it introduced a branch of Dick novels in which mental illness plays a significant role. Given that he, himself, suffered from one or more mental illnesses during his life makes this addition unsurprising.

Dick’s work has had tremendous success with Hollywood, giving old works new life. His 1968 classic novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was adapted by Ridley Scott in 1982 into the film Blade Runner – while at first Dick was entirely opposed to the adaptation, when he read a revised script, he immediately saw the film’s enormous potential. Unfortunately, he died of a stroke four months before it was released. Other notable adaptations include Total Recall (“We Can Get it for You Wholesale”), Minority Report, Paycheck, The Adjustment Bureau (“The Adjustment Team”), and, most recently, Amazon’s The Man in the High Castle series and Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams anthology, the latter adaptations of 10 of the author’s short stories.

So much more can be said of Dick and his work, including his paranoia, his drug use, and his belief that he was being contacted by an extraterrestrial “life force” appearing as a pink beam of light, all of which appeared in some fashion in his stories. But the best summation of the man and his view of writing comes from Dick himself: “I love writing. I love it. I love my characters. They’re my friends. When I finish a book, I go into post partem, never to hear them speak again, never to see them struggling and trying. And I’ve lost them, because a writer doesn’t really reread his own works. But then, other people will read them.”[3]

And read them we do.

Citations:

[1] An online community for followers of Philip K. Dick. Retrieved from https://philipdick.com/biography/

[2] Dick, Philip K. (October 22, 2011). “An Interview with America’s Most Brilliant Science-Fiction Writer” Interview by Joe Vitale. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_K._Dick

[3] Cover, Arthur Byron. (February 1974). “Vertex Interviews Philip K. Dick.” Vertex, Vol. 1, no. 6. Retrieved from https://urbigenous.net/library/vertex_pkd.html