[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

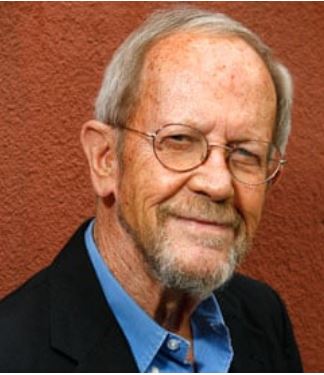

In a 2011 interview with Justified producer Graham Yost, Elmore Leonard said, “The way I write is always from the character’s point of view. I make up my characters as I go along, and I listen to them. They’ve got to be able to talk. If they can’t talk, they’re out. Or they get shot.” And, boy, did Leonard’s characters talk – it was one of the defining features of his work.

Leonard was born in 1925 in New Orleans. He became interested in writing 10 years later, after he read a serialization of All Quiet on the Western Front in the Detroit Times. That inspired him to write a play based on the novel for his fifth-grade classroom. In high school he wrote a couple of stories for the school paper, but he was more absorbed in reading at the time. When he graduated in 1943, he joined the navy, serving with a Seabee unit in the South Pacific, but he left the service in 1946 to enroll at the University of Detroit, where he picked up writing again, entering short story contests. He graduated in 1950 with majors in English and philosophy and earned his first professional writing credit a year later with a short story for Argosy magazine called “Trail of the Apache.”

Leonard started out by writing westerns, because at the time that was the most financially viable genre. His first novel, The Bounty Hunters, was published in 1953. He followed it with four more novels during the next eight years as well as numerous short stories, mostly westerns; they appeared in publications including Zane Grey Western and The Saturday Evening Post. One of those early novels was Hombre, later adapted for film; it was selected as one of the best Westerns of all time in 1961 by the Western Writers of America – a singular honor. With that recognition, Leonard felt secure enough to quit his day job and devote all his energies to his novels.

As the market for westerns began to diminish, however, Leonard found work writing educational films for Encyclopaedia Britannica, industrial films for corporations, and advertising and sales copy. Then he made the switch from westerns to crime with the publication of The Big Bounce in 1969; however, it wasn’t until Glitz was published in 1985 that he came to national attention. And it wasn’t until 1995’s successful film adaptation of Get Shorty that Hollywood became intensely interested in adapting his work.

Leonard’s crime novels are intriguing, as they don’t fit the “accepted norm” with its sequence of atrocity, mystery, an investigator battling the establishment, and a satisfying resolution. He relied on characters who didn’t fit societal norms – miracle workers, superwomen, even men who would dive 80 feet from a platform just for kicks. He was also interested in people who fell below the normal standards of humanity, such as gangsters, bank robbers, and people who lived off the beaten path. What is also interesting is that he allowed these characters to operate without imposing a moral judgment on them. It’s often been said that it’s hard to tell who the good guys and who the bad guys are in his novels – the good guys do bad things sometimes, and the bad guys redeem themselves in surprising ways. In a world filled with all kinds of criminality, the criminal who carries out his robbery or murder with wit and flair can become the object of our admiration. Above all, the allure of intelligence and the ability to speak articulately draw the audience in, and we look favorably on the man who speaks best and most wittily.

Leonard was fascinated with the mechanics of writing, and he definitely wanted his readers to share that interest. His characters play with words, speaking smartly, investigating the different nuances that words can have. And those investigations revealed more about who and what each character was more than any amount of exposition could do. He also viewed the rhythm of a character’s speech to be more important than anything they actually said. “If it sounds written, it’s wrong,” he said. He went on to explain the importance of dialogue: “I try to leave out the parts the readers skip. Think of what you skip reading a novel: thick paragraphs of prose you can see have too many words in them. I’ll bet you don’t skip dialogue.”

Leonard, a dedicated writer who always wrote his books in longhand, had a number of rules for how to approach the craft, and he laid out his Top 10 in a 2001 New York Times article. They have since become almost a “bible” for aspiring writers. These included such important ideas as “Never use a verb other than “said” to carry dialogue,” and “Never use an adverb to modify the verb “said” . . . To use an adverb this way (or almost any way) is a mortal sin. The writer is now exposing himself in earnest, using a word that distracts and can interrupt the rhythm of the exchange.”[1] He reportedly said that if an adverb ever made its way into his writing, he would have it “killed.”

“My most important rule is one that sums up the 10,” Leonard said in the same article. “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it. Or, if proper usage gets in the way, it may have to go. I can’t allow what we learned in English composition to disrupt the sound and rhythm of the narrative. It’s my attempt to remain invisible, not distract the reader from the story with obvious writing.

“If I write in scenes and always from the point of view of a particular character – the one whose view best brings the scene to life – I’m able to concentrate on the voices of the characters telling you who they are and how they feel about what they see and what’s going on, and I’m nowhere in sight.”[1]

Three of Leonard’s books were nominated for the Edgar Allan Poe Award by the Mystery Writers of America: The Switch, in 1978; Split Images, in 1981; and LaBrava, which won for Best Novel in 1983. Leonard himself was awarded the first annual International Association of Crime Writers’ North American Hammett Prize in 1991, and, in 1992, the Mystery Writers gave him the Grand Master Award, which “is presented only to individuals who, by a lifetime of achievement, have proved themselves preeminent in the craft of the mystery and dedicated to the advancement of the genre.”

“I’ve been doing this for 50 years. I still enjoy it,” Leonard told The Hollywood Reporter in 2012. “Writing never felt like work to me.”

Citation:

[1] Leonard, Elmore. (July 16, 2001). “WRITERS ON WRITING: Easy on the Adverbs, Exclamation Points and Especially Hooptedoodle.” Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2001/07/16/arts/writers-writing-easy-adverbs-exclamation-points-especially-hooptedoodle.html