[Editor’s note: This is the twelfth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

The Meroïtic script was used from the 2nd century BCE until the 5th century CE in the Kingdom of Kush, a region of the Nile Valley that extended from Philae in Nubia to around Khartoum in Sudan. After that time, the script was replaced by Nubian.[1]

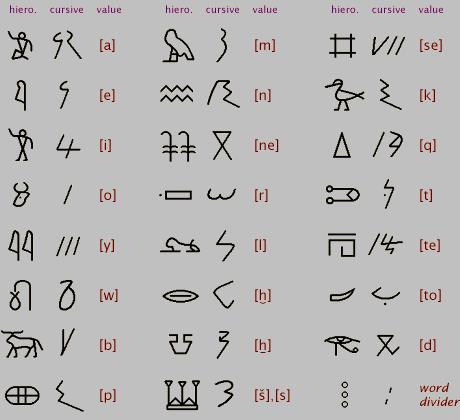

There were two major forms of Meroïtic scripts, the hieroglyphic and the cursive, both descended from the Egyptian writing systems. The hieroglyphic signs were based on the ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics and were written in columns that read from top to bottom. Almost all of the examples we have of this script appear on monuments of some kind. The cursive form arose somewhere around 185 BCE and was based on the Egyptian demotic script, the alphabetic writing form used by the common people in everyday life. It was written in horizontal lines that generally read from right to left but could be written from left to right. You can determine the proper direction of the text by looking at which way the figures face. If the sign faces right, then you start from the right and move left; if the sign faces left, then you start from the left and move right.[1][2]

Meroïtic hieroglyphs and cursive writing

When scholars studied the signs’ phonetic values, they discovered a rather strange mixture of alphabetic and syllabic signs, which led them to conclude that the system was really a minimalistic syllabary. The signs that appear to represent consonantal sounds are really combinations of that particular consonant and the vowel ‘a,’ which was used only at the beginning of words (where one might expect a syllabic ‘a’ to occur). These same signs became purely consonantal if they were followed by the vowels ‘i,’ ‘e,’ or ‘o.’ In addition, to represent a simple consonant that contained no vowel sound, the ‘e’ symbol was written after the consonant to indicate the lack of the default ‘a’ vowel.[1]

The largest share of deciphering Meroïtic was done by Francis Llewellyn Griffith (1862–1934), an English scholar. He was able to determine the phonetic value of the signs by comparing proper names in Meroïtic texts with those in Egyptian. It’s important to understand, though, that while we can now read the Meroïtic texts, we can’t understand what they mean. Like the Etruscan writing we looked at last time, the Meroïtic script is interesting primarily because it is an isolate as far as we know. It has no known relatives or daughter languages with which we can compare the writing, and there are no dictionaries or grammars that we’ve found to help decipher the meaning of the text. The phasing out of its use in the 5th century pretty much rendered it a dead and undecipherable language from that point forward.

Next up: Runes and Futhark

Citations:

[1] Lo, Lawrence. (2012). “Meroïtic.” AncientScrips.com. Retrieved from http://www.ancientscripts.com/meroitic.html.

[2] Ager, Simon. (2018). Meroïtic alphabet. Omniglot.com. Retrieved from https://www.omniglot.com/writing/meroitic.htm.

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

4 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 11: Meroïtic Script, another Undecipherable Language”