[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

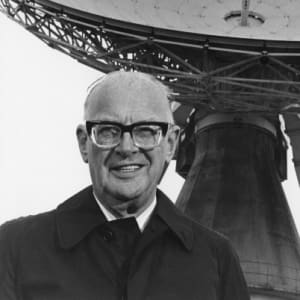

“The universe is not only stranger than we imagine, it’s stranger than we can imagine.” So said Arthur C. Clarke, pioneering scientist and one of the “Big Three” science fiction writers of the genre’s “Golden Age,” alongside Isaac Asimov and Robert Heinlein.

Clark was born in 1917 to a farming family in the coastal town of Minehead, England. At an early age, he became fascinated with both science and astronomy, using a homemade telescope to study the stars. He also enjoyed reading science fiction stories from magazines like Astounding Stories. However, when his father passed away suddenly, the family experienced severe financial difficulties, and, despite his inquisitiveness, Clarke was unable to attend a university; instead he headed to London to find work.

While he found a job as a government bureaucrat, though, his head was still roaming amongst the stars. He discovered and joined the British Interplanetary Society, which promoted the idea of traveling through space long before it was generally considered plausible. He contributed articles to its newsletter and started to try his hand at writing science fiction. Clarke’s work was cut short by the outbreak of World War II. However, his service as a technician with the Royal Air Force provided a wonderful opportunity to delve further into technology. During his service, he became among the first servicemen to use radar to guide aircraft landings in inclement weather.

Clarke’s service also proved fundamental in two of his earliest writing efforts. In 1945, Wireless World magazine published his article “Extra-Terrestrial Relays.” In it he speculated about how a geostationary satellite system could be used to transmit radio and television signals around the world. This speculation was extremely prescient, as today we rely heavily on geostationary communications satellites for everything from cell phones to internet to GPS coordinates. It was so prescient that a geostationary orbit is now also referred to as a “Clarke Orbit.” The next year he published his first SF short story, “Rescue Party,” in Astounding Science Fiction.

After returning home, Clarke was able to pursue his higher education, receiving a fellowship to King’s College in London. He graduated in 1948 with honors in math and physics and started to make a name for himself, both as an author and as a scientist. He published his first book in 1950 while an assistant editor for Science Abstracts magazine. It was called Interplanetary Flight; and in it he discussed the possibilities of space travel. His first full-length novel, Prelude to Space, was published the following year; two years later he followed that up with two science-fiction works, Against the Fall of Night and Childhood’s End. The latter is arguably his most successful story and has stood up well over time.

Clarke’s writing won him acclaim as a novelist and prominence as a revolutionary scientific thinker. Members of the scientific community often sought his input and guidance, and he worked with the Americans to help design spacecraft and assist in the development of meteorological satellites. He wasn’t limited to a single field, though. His space travel books usually contained information about other aspects of science and technology, such as computers and bioengineering, and he made a number of astounding predictions. These predictions culminated in a series of magazine essays started in 1958, which were later compiled into 1962’s Profiles of the Future, and worked on a timetable up to the year 2100. In addition to his thoughts of a “global library” — think internet — he outlined what would become “Clarke’s Three Laws.”

Law #1: Clarke predicted global satellite TV broadcasts that would be able to cross national boundaries and make hundreds of channels available to anyone, anywhere in the world.

Law #2: Clarke described a “personal transceiver, so small and compact that every man carries one.” He wrote: “the time will come when we will be able to call a person anywhere on Earth merely by dialing a number.”

Law #3: The transceiver Clarke envisioned would also include means for global positioning so “no one need ever again be lost.” This small device, he believed, would appear somewhere in the mid-1980s, just about the time cell phones and GPS tracking became available to the general public.

During a 1974 interview with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Clarke was asked both how he believed the computer would change the everyday person’s life and what their life would be like in the year 2001. Online banking and shopping, as well as many other automated services, were some of his responses. When the interviewer asked him how the man’s son’s life would differ from his own, he responded, “He will have, in his own house, not a computer as big as this, [points to nearby computer], but at least, a console through which he can talk, through his friendly local computer and get all the information he needs, for his everyday life, like his bank statements, his theatre reservations, all the information you need in the course of living in our complex modern society, this will be in a compact form in his own house … and he will take it as much for granted as we take the telephone.” Welcome to the Computer Age.

Clarke’s greatest collaboration — or at least the one for which he’s best known — came in 1964, when film director Stanley Kubrick approached him with the intent to create a science-based film. The two chose Clarke’s 1951 short story “The Sentinel” as the springboard for what would eventually become 1968’s classic 2001: A Space Odyssey, often cited as one of the greatest movies ever made. Clarke and Kubrick received an Academy Award nomination for their jointly penned script, and they collaborated on developing the story into a novel which came out the same year. At the end of the 1960s, Clarke took part in a real-life space odyssey — he was chosen to join Walter Cronkite as a commentator of the Apollo 11 lunar landing for the CBS network.

In the mid-1950s Clarke began to develop another passion — the world under the oceans. In 1956 he moved to Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), becoming a skilled diver, photographing the native reefs, and even managing to discover the ruins of an ancient temple on the sea bottom. In addition to writing about this new frontier, Clarke set up several diving-related ventures with Mike Wilson, his long-standing business partner.

Clarke, who died of post-polio syndrome in 2008, is best remembered though for his passion for science and space. He won his first Hugo Award in 1956 for his short story “The Star.” In 1961 he received a Kalinga Prize, an honor given by UNESCO for popularizing science, and, together with his science fiction writings, that earned him the title of the “Prophet of the Space Age.” His 1973 novel Rendezvous with Rama won both the Nebula and Hugo awards, as did 1979’s The Fountains of Paradise. In 1985 the Science Fiction Writers of America awarded him the title of Grand Master. He was knighted by the British high commissioner in Sri Lanka; he was given that country’s highest civil honor, the Sri Lankabhimanya; and he saw the founding of the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education.

As prescient as he was about our world and its technology, how did he view the possibility of intelligent life beyond our world that he wrote so much about? “Two possibilities exist,” he said. “Either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” His words are his legacy, inspiring generations of explorers who will follow where they lead into an exciting new future.