[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

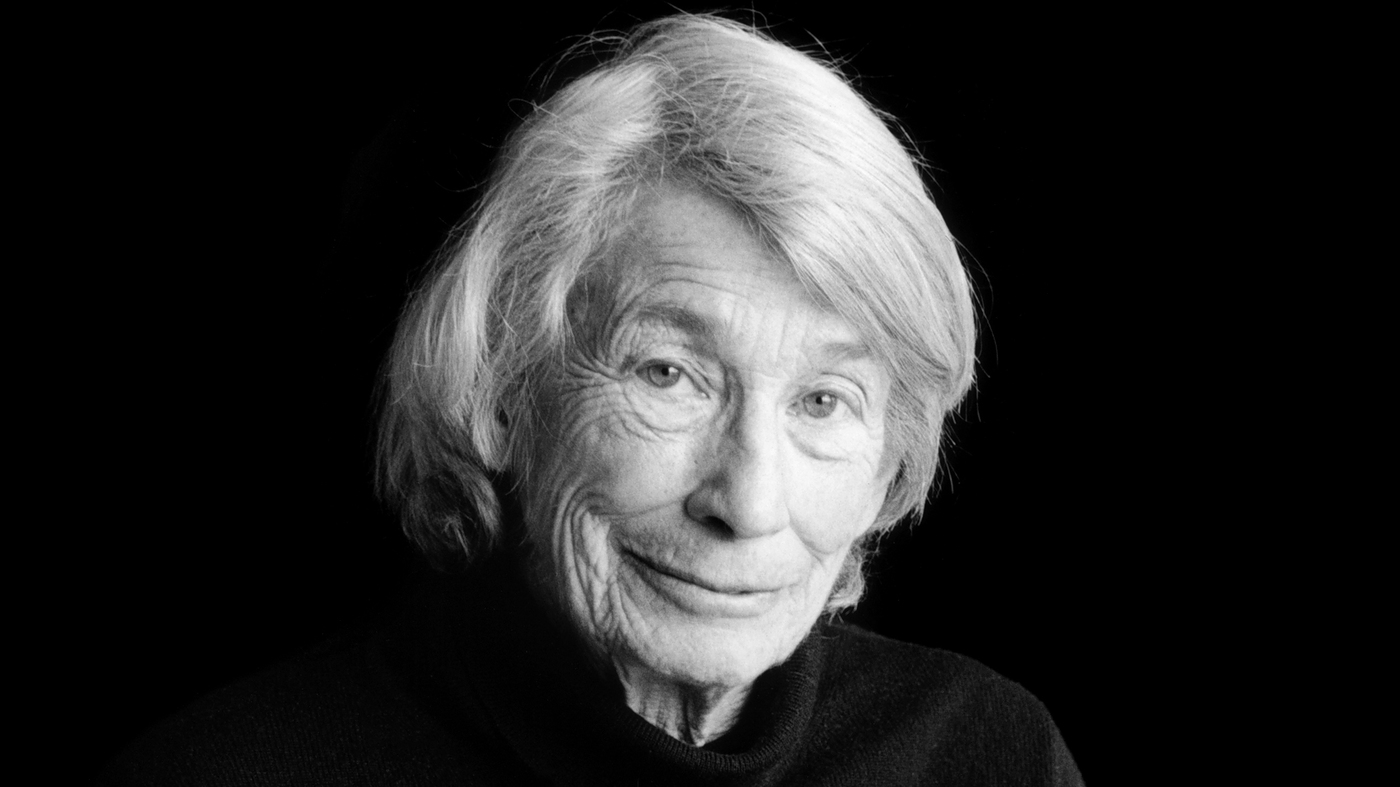

“I had a very dysfunctional family, and a very hard childhood,” poet Mary Oliver told O: The Oprah Magazine in 2011. “So I made a world out of words. And it was my salvation.”

Oliver was born in 1935 in Maple Heights, Ohio to a father who was a teacher and a mother who was a homemaker. Both were committed to raising her in close proximity to nature and taught her to experience the environment around her fully. Remembering her formative years, Oliver reminisced, “It was pastoral, it was nice, it was an extended family. … I don’t know why I felt such affinity with the natural world except that it was available to me, that’s the first thing. It was right there.”

After graduating high school, Oliver attended The Ohio State University in Columbus, but she remained there for just a year. Next, she attended Vassar College, a woman’s college located in Poughkeepsie, New York. She didn’t graduate from this institution either, but she spent a great deal of her time writing. “To keep writing was always a first priority….” she commented in a rare interview (she wanted her work to speak for itself). “I worked probably twenty-five years by myself…. Just writing and working, not trying to publish much.” It wasn’t until 1983 that Oliver first decided to publish, and her poetry collection, American Primitive, won the 1984 Pulitzer Prize.

Oliver wasn’t a completely unknown figure in the writing world upon her first publication, although the general public was unfamiliar with her work at this time; she had spent a number of years prior to publication in academia. In 1972, she chaired the writing department of the Fine Arts Workshop in Provincetown, Massachusetts, where she lived, and she was awarded the Mather Visiting Professorship at Case Western Reserve University about 10 years later. In addition, she won two fellowships, one from the National Endowment of the Arts during 1972–1973, and the other from Guggenheim during 1980–1981.

Quite simply, writing was in Oliver’s blood. “I decided very early that I wanted to write,” she commented. “But I didn’t think of it as a career. I didn’t even think of it as a profession…. It was the most exciting thing, the most powerful thing, the most wonderful thing to do with my life. And I didn’t question if I should — I just kept sharpening the pencils!”

Her poems, most of which grew from her early and continuing connection with nature and the beauty of the town in which she lived, are filled with both unadorned language and accessible imagery, put forth in a conservative yet conversational style. These attributes, combined with the works’ relative shortness, seemed to endear her to a wide range of people, from clerics to therapists to composers. Oftentimes, throngs of people would turn out for her public readings, elevating her to the status of a “celebrity” book star. The following is just one example of the simplicity and beauty of her natural studies:

Breakage

I go down to the edge of the sea.

How everything shines in the morning light!

The cusp of the whelk,

the broken cupboard of the clam,

the opened, blue mussels,

moon snails, pale pink and barnacle scarred—

and nothing at all whole or shut, but tattered, split,

dropped by the gulls onto the gray rocks and all the moisture gone.

It’s like a schoolhouse

of little words,

thousands of words.

First you figure out what each one means by itself,

the jingle, the periwinkle, the scallop

full of moonlight.

Then you begin, slowly, to read the whole story.[1]

Oliver often described her work as the observation of life, and she relayed those observations with an almost mystical spirituality. Readers were also drawn to her poems for their sense of confiding intimacy; to read those poems is to take an active role in the observation and the expression of the author’s environment as she walked in the forest or along the seashore. Her walks — and her observations — became so frequent that she prepared for the inevitable need to write on her excursions by secreting pencils in the woods near her home.

Oliver’s poetic work continued to receive acclaim following her brilliant 1984 debut. Her second collection, House of Light, won 1990’s Christopher Award and the L. L. Winship/PEN New England Award. Her third collection, New and Selected Poems, won the National Book Award. New and Selected Poems contained entries spanning more than 30 years of writing, yet Oliver managed to infuse each individual poem with a similar voice. She later commented that if she could start over again, she would “just write one book and keep adding to [it].” All told, she released ten volumes of poetry along with three books of prose. Her book-length poem, The Leaf and the Cloud, was split into two sections; the first was published in the 1999 release of Best American Poetry, and the second in its 2000 release.

Oliver’s work was not limited to poetry. She also published essays, which appeared in numerous periodicals, and she served as editor of Best American Essays 2009. In addition, she contributed her knowledge and skills to new generations of writers, both as the writer of books on poetic craft and as a teacher. A Poetry Handbook and Rules for the Dance are widely found in writing programs, and she led workshops, as well as held residencies at institutions such as Case Western Reserve University, Bucknell University, and Sweet Briar College. From 1995 to 2000 she also held the Catharine Osgood Foster Chair for Distinguished Teaching at Bennington College.

Despite her prodigious output and numerous awards, Oliver was never one to rest on her laurels, instead continuing to work on her craft up until her death in early 2019. “I never have felt yet that I’ve done it right,” she once said. “This is the marvelous thing about language. It can always be done better.”

Citation:

[1] Retrieved from: https://bookriot.com/2019/01/16/mary-oliver-poems/