[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

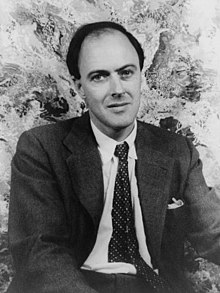

Roald Dahl was born in 1916 in Llandaff, South Wales to Norwegian parents. He wrote both children’s fiction and short stories for adults, and is perhaps best known as the author of the 1964 children’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

As a youngster, Dahl was an avid reader, especially awed by fantastic tales of heroism and triumph, as well as ghost stories. Among his favorite authors were Rudyard Kipling, Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, and Frederick Marryat, and their works made a lasting impression on his life and writing.

Another great influence on his writing came from his mother – Sofie Dahl would gather Roald and his sisters and tell them the traditional Norwegian myths and legends. In an interview much later on, he commented: “She was a great teller of tales. Her memory was prodigious and nothing that ever happened to her in her life was forgotten.” When Dahl wrote “The Witches,” he created a grandmother character that he claimed was based directly on his own mother, as a tribute.

Dahl’s father died when he was four, and his mother sent him to an excellent English private school per her husband’s request. But Dahl was an imp and a troublemaker, and he was moved from one institution to the next as his behavior caught up with him. He would later describe his school years as “days of horrors” filled with “rules, rules and still more rules that had to be obeyed,” which inspired a great deal of his gruesome fiction. He was not a good student, yet his mother offered him a chance to attend Oxford or Cambridge University. His reply, which he included in his Boy: Tales of Childhood, was, “No, thank you. I want to go straight from school to work for a company that will send me to wonderful faraway places like Africa or China.”

And that’s exactly what he did. Dahl took a position with the Shell Oil Company in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Africa. In 1939 he joined a Royal Air Force training squadron in Nairobi, Kenya, after which he served as a fighter pilot in the Mediterranean during World War II (1939–45). He suffered severe head injuries in a plane crash; after he recovered, he was sent to Washington, D.C. to be an assistant air attache (a technical expert who advises government representatives). It was there Dahl began to write. He first published a short story in the Saturday Evening Post and then followed it with many stories in other magazines. Dahl told Willa Petschek in the New York Times Book Review that “as I went on, the stories became less and less realistic and more fantastic. But becoming a writer was pure fluke. Without being asked to, I doubt if I’d ever have thought of it.”

Dahl wrote his first children’s story, “The Gremlins,” in 1943, and he invented a new term in the process. In the air force, “gremlins” were small creatures that inhabited fighter planes and bombers and were responsible for all crashes; now they became anything that stirred up trouble. Throughout the 1940s and into the 1950s, Dahl continued to write short stories, but for adults, and he gained a reputation as the author of deathly tales that had unexpected twists. His efforts earned him three Edgar Allan Poe Awards from the Mystery Writers of America.

Yet Dahl never left the children’s stories behind. In 1953 he married actress Patricia Neal; the marriage ultimately ended up in divorce, but they had five children together. He made up stories for them each night before they went to bed, stories which became the basis for his career as a children’s writer. His first publication was 1961’s James and the Giant Peach, a fantastic tale of a young boy who travels thousands of miles in a house-sized peach with a group of rather strange companions. Inventing stories night after night, Dahl insisted, was perfect practice for his trade. He told the New York Times Book Review: “Children are … highly critical. And they lose interest so quickly. You have to keep things ticking along. And if you think a child is getting bored, you must think up something that jolts it back. Something that tickles. You have to know what children like.”

One way that Dahl tickled his readers was taking vicious revenge on cruel adults who had harmed children; a perfect example is in 1988’s Mathilda. Many critics objected to his treatment of adults, but Dahl explained in the New York Times Book Review that the children who wrote to him always “pick out the most gruesome events as the favorite parts of the books.… They don’t relate it to life. They enjoy the fantasy.” He also said that his “nastiness” was perfectly acceptable. “Beastly people must be punished.”

In Trust Your Children: Voices against Censorship in Children’s Literature, Dahl said that adults may be disturbed by his books “because they are not quite as aware as I am that children are different from adults. Children are much more vulgar than grownups. They have a coarser sense of humor. They are basically more cruel.” Dahl often commented that the key to his success with children was that he joined with them against adults. “The writer for children must be a jokey sort of a fellow,” Dahl commented to Writer. “He must like simple tricks and jokes and riddles and other childish things. He must be … inventive. He must have a really first-class plot.”

Dahl was also famous for his inventive, playful use of language. He would invent new words by scribbling down actual words and then swapping letters around, as well as adopting spoonerisms and malapropisms. Lexicographer Dr. Susan Rennie commented on his technique:

“He didn’t always explain what his words meant, but children can work them out because they often sound like a word they know, and he loved using onomatopoeia. For example, you know that something lickswishy and delumptious is good to eat, whereas something uckyslush or rotsome is definitely not! He also used sounds that children love to say, like squishous and squizzle, or fizzlecrump and fizzwiggler.”

When Dahl received the 1983 World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, he encouraged his children and all his readers to let their imaginations run free. His daughter Lucy stated “his spirit was so large and so big he taught us to believe in magic.”

And that’s a large part of what continues to make his books so magically appealing to this day.