[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

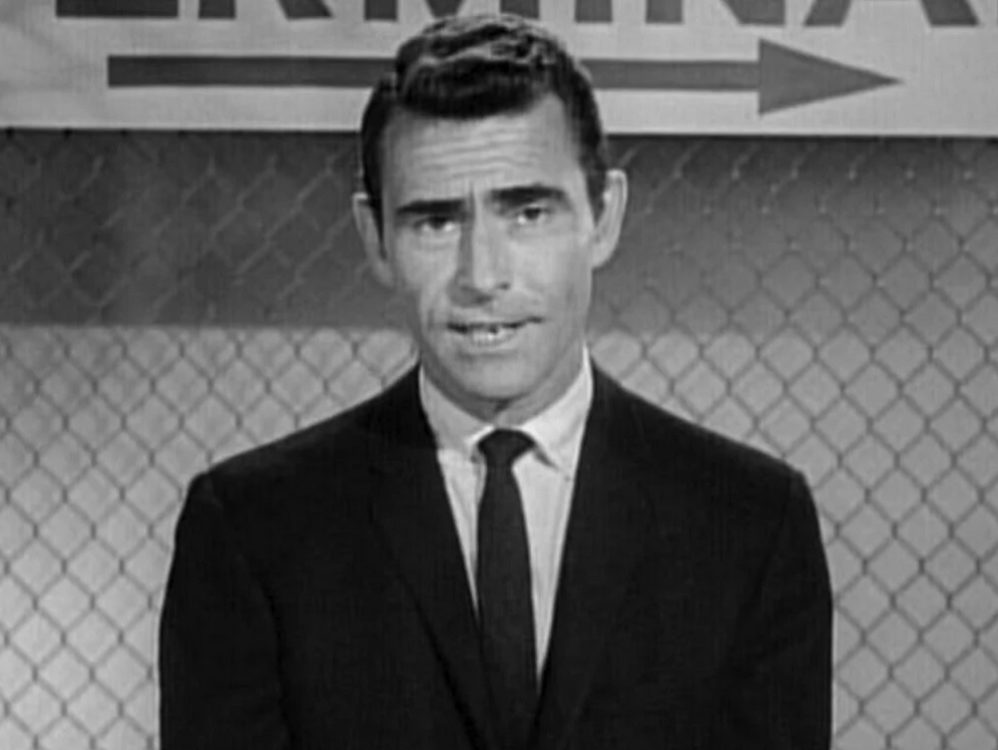

No, you haven’t entered the “Twilight Zone;” you’ve entered the life of Rod Serling, that show’s creator and one of television’s most prolific writers. He believed that his role as a writer was to “menace the public conscience,” and he used radio, television, and film as vehicles of social criticism.

Rodman Edward Serling was born in 1924 and grew up in Binghamton, New York. After graduating from high school, he enlisted in the United States Army, serving in New Guinea as well as in the Philippines. He suffered a severe shrapnel wound to his knee, for which he was awarded the Purple Heart, but the mental toll from the war proved more severe and more lasting – when he received his discharge in 1946, he was “bitter about everything and at loose ends,” and he suffered from flashbacks, nightmares, and insomnia for the remainder of his life.

Serling took advantage of the G.I. Bill, though, to enroll at Antioch College. In the late 1940s, the school was famous for its loose social rules and a unique work-study curriculum, and Serling was stimulated by the liberal intellectual environment. He began to feel “the need to write, a kind of compulsion to get some of my thoughts down.” In addition, he was inspired by the words of Horace Mann, a Unitarian educator and the first president of Antioch College: “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” Those words made such an impression on him, that Serling would later feature them, as well as a statue of Mann, in the 1962 “Twilight Zone” episode “Changing of the Guard.”

Serling graduated in 1950 with a degree in literature and found a job as a staff writer with radio station WLW in Cincinnati, Ohio. However, he was passionately motivated to freelance; he worked days at the station and nights at home writing. He started by writing short stories, which dealt primarily with the war, then moved on to scripts. By 1952, his freelance income permitted him to quit WLW and focus on writing full-time. He moved to Manhattan, where most of the early television shows were produced. There he won Emmy Awards for three of his teleplays: “Patterns” in 1955; “Requiem for a Heavyweight” in 1956; and “The Comedian” in 1957.

Uncompromising in his vision, he infused his work with his passion and experience – his message in “Patterns,” for example, was that “every human being has a minimum set of ethics from which he operates. When he refuses to compromise these ethics, his career must suffer, when he does compromise them, his conscience does the suffering.” It was a theme he would return to time and again.

By the late 1950s, the days of live television were numbered. In addition, the industry shifted location from New York, with its theater-oriented view, to Hollywood, where there was more money, equipment, and talent available to produce scripts for the small screen. Serling believed that “of all the media, TV lends itself most beautifully to presenting a controversy,” and he found that with television he could “take a part of the problem, and using a small number of people, get my point across.” In 1957, Serling left New York and moved to Pacific Palisades, a suburb of Los Angeles.

As he started developing scripts, Serling quickly realized that to get his point across he had to create stories with controversial themes. He was used to doing this; however, he found that the corporate sponsors weren’t, and they didn’t want their products associated with anything viewers might deem offensive. The issue frustrated Serling greatly, and in 1959 he commented: “I think it is criminal that we are not permitted to make dramatic note of social evils that exist, of controversial themes as they are inherent in our society.”

As a way around such a hostile creative environment, Serling began to gravitate toward writing science fiction and fantasy. In those genres, he could pretty much say what he wanted in the way he wanted. The sponsors would routinely approve stories containing controversial situations if those situations took place on fictional worlds; somehow they didn’t make the connection that the worlds and ideas were merely stand-ins for our own. It was then that Serling began to create what became his signature piece, “The Twilight Zone,” a series that offered not only an opportunity to create new worlds, but also a chance to avoid unwanted censorship. The series enjoyed a five-year run, from 1959 to 1964; Serling and the other writers received unprecedented artistic freedom throughout, and he won two more Emmys for his work.

On October 10, 1959, “The Twilight Zone” debuted with the episode, “Where is Everybody?” Serling pitched this episode using Orson Welles as narrator, but when Welles asked for too much money to do the show, the producers decided it would be easiest if Serling did the opening narration himself. In addition to his on-screen appearances, he wrote or adapted 99 of the total 156 episodes himself. And, as with his other work, he used the episodes to address dozens of social issues, including prejudice (“The Eye of the Beholder,” 1960), loss of identity (“Mirror Image,” 1960), capital punishment (“Execution,” 1960), censorship (“The Obsolete Man,” 1961), ageism (“The Trade-Ins,” 1962), and social conformity (“Number Twelve Looks Just Like You,” 1964). In the closing words to the 1961 episode “The Shelter,” he stated what he believed to be humanity’s greatest challenge: “No moral, no message, no prophetic tract, just a simple state of fact: for civilization to survive, the human race has to remain civilized.”

As excited as he was about the series, Serling nevertheless accepted a year-long teaching position at Antioch in 1962. He said he felt he needed to “regain my perspective, to do a little work and spend the rest of my time getting acquainted with my wife and children.” There he taught writing, drama, and a survey course about the “social and historical implications of the media,” the latter a subject with which he was intimately familiar.

But television, especially the day-to-day grind of producing a weekly series, can be grueling, and Serling claimed “television has left me tired and frustrated.” As a result, he began to write more scripts for the movies, still using the work as a platform for social discourse. For example, “Seven Days in May,” which came out in 1964, showcased his passion for nuclear disarmament and peace – “If you want to prove that God is not dead, first prove that man is alive,” was how he described it. He also penned the 1968 version of Pierre Boulle’s “The Planet of the Apes,” which tackled both racism and anthropocentrism.

He continued to write for television, but he never enjoyed the same success as he had with “The Twilight Zone.” “The Loner,” which ran from 1965–1966, and “Night Gallery,” which aired from 1970–1973, were two examples of his later work, but they left him feeling bitter about the experience. He had little creative control on either one of them, and he said of “Night Gallery” that “It is not mine at all. It’s another species of a formula series drama.” It was a bitter end to a magnificent career.

Next week: Stan Lee