[Editor’s note: This is the first of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today.]

Today, we take reading and writing for granted – we look at the newspaper in the morning, we peruse a good book during our commute to and from work or while relaxing on the sofa, and we hit the textbooks when we’re in school. But this has not always been the case. While human beings are hard-wired for oral language, our neural circuitry had to change and adapt in order to allow us to read and write [to read our blog post on this topic, click here]. This means someone, somewhere, had to develop a system of codifying information so that another person could read and understand what was written, providing individual access to accumulated cultural experiences, knowledge and information.[1]

We know that the most primitive examples of writing, pictographs painted on the walls of caves and on rocks, arose about 40,000 years ago in numerous parts of the world. Scientists have carbon dated these paintings in southwest Africa, Australia, and southwest Europe to that early time period. Cave art was a simple way of describing an object by drawing a picture that everyone could recognize as that object; however, it had no basis in the oral language of the people creating it. True writing, where symbols denoted a complex idea and where they also reflected spoken sounds and words, developed much later. True writing arose independently at least three – and maybe four – times throughout history. These were in Mesopotamia somewhere around 3300 BCE, where the Sumerian people created a type of writing called cuneiform; in ancient Egypt either at the same time as the Sumarians or slightly later, where hieroglyphs were mixed with “common” scripts; in ancient Mexico sometime before 400 BCE by the Olmec people, whose script became a precursor to the Maya glyphs used between 200 and 1500 CE; and in North China around 1200 BCE, where the symbols eventually became what we know as modern Chinese characters. These are all examples of true writing because in each archaeologists believe that the pictures used began to denote syllables of sound instead of just conveying a straightforward meaning.

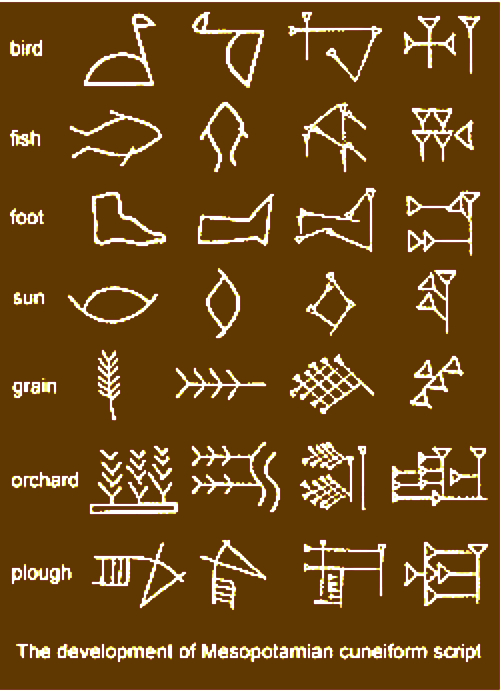

The Sumerians lived in the delta of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers where they built city-states sometime after 3500 BCE. Their language was neither Indo-European nor Semitic, and it is not known to be related to any other language. The “proto-literate” period of Sumerian writing spans the time from 3300 to 3000 BCE. Records from this time (the oldest object is known as the Kish tablet) are purely logographic (an abbreviated symbol for a frequently recurring word or phrase, such as the modern &, which denotes “and”) with phonological content. Tokens with a pictographic image were used well before true writing developed (at least 9,000 years ago) to label produce and other goods. From there the Sumerians progressed to creating impressions with the tokens on clay tablets, and finally they used a blunt reed called a stylus to draw the tokens’ images on those tablets. As the impressions left by the stylus were wedge shaped, this type of writing was called cuneiform, wedge-writing. It flourished between 3100 and 2000 BCE then fell into disuse. It wasn’t until the last century or so that scholars were able to decode and read the cuneiform writing on the tablets.

The first proven use of cuneiform to denote the sounds of the Sumerian language and not just an object appears in clay tablets found at Jemdet Nasr in present-day Iraq, dating back to around 3100 BCE. As an example, on one of these tablets the Sumerian symbol for arrow was used to convey the word meaning “life.” There is no logical connection between the image of an arrow and the concept of life, but when you look at the language’s sound, the reason for using the arrow pictograph here becomes understandable. The Sumerian word for arrow was “ti,” while the word for life was “til,” a near homonym. The concept of life is a difficult thing to draw, so some scribe took advantage of similarity in the words’ sounds (their homonymy) and used an existing pictograph to denote the sound of the syllable ti independent of the pictograph’s original meaning. Similarly, the pictogram for “reed” was used to convey the unrelated concept of “reimburse;” in the Sumerian language, both were pronounced something like “gi.” In this way, pictograms began to be used as sound symbols.

The transition to full writing in Sumeria occurred sometime between 3500 and 3000 BCE, as more signs came to be used as representations of sounds. And, as they became sound symbols, most pictographs were stylized and eventually lost their iconographic form altogether. When the transition was complete, it became possible to symbolize all the syllables of the Sumerian language and to construct written words, no matter how abstract their meaning. It was at this time that true writing was born.

The morphological structure of the Sumerian language, where many single syllables were separate words or at least separate morphemes, undoubtedly made the process of creating a writing form much easier; it also undoubtedly facilitated the transfer of pictograms into sound symbols, or graphemes. A language like English, which contains a complicated syllable structure as a result of its very convoluted origins, would have been nearly impossible to create using pictures for each syllable. Before we take up the history of how written English did come about, though, we need to understand more about how the earliest forms of writing developed.

Next up: Egyptian hieroglyphics

Citation:

Johnson, Genevieve Marie. (May 2015). “The Invention of Reading and the Evolution of Text.” Journal of Literacy and Technology. Volume 16, Number 1.

33 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 1: The Origins of Writing”