[Editor’s note: This is the seventeenth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. It is also the third of a three-part discussion of the rise of printing and its effect on various civilizations. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

Last week we continued our discussion of the developments in printing and written communication, up through the introduction of Gutenberg’s printing press. This week we’re going to look at how printing affected civilizations all over the world, from that point to the modern age.

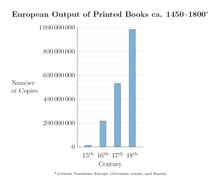

As we’ve seen, printing in one form or another developed around the ancient world primarily to advance economic pursuits and to share knowledge among religious leaders. No innovation in the field, however, had as much of an impact as Gutenberg’s printing press in a wide range of areas. It changed the map of Europe, weakened the Catholic Church’s power, and shifted education and the accumulation of knowledge from the religious realm to the secular – all within a period of less than 50 years. While in 1455 no printing presses existed in Europe, by 1500 they were operating in 245 different cities. While before 1455 there were no printed texts in Europe, by 1500 over 20 million books existed – one for every five people.[1]

Rise in number of European books following Gutenberg’s Press

Most innovations that change social norms do so by first working within the existing norm, and that was the case with Gutenberg’s press. His first, and intended, client was the Catholic Church, and it was in this context that his first printed book was the Bible. Prior to this time, religious scribes recorded and transcribed all knowledge and teachings of the Church; however, this was a tedious, time-consuming, and error-prone process. Gutenberg’s intent was to sell his Bibles in an “unfinished” form to monasteries and religious centers throughout Europe, and scribes would add in the illumination at a later time.

Leaders of the Catholic Church stood behind the idea of Gutenberg’s press, believing that mass-producing copies of its teachings would strengthen its power and authority. As most of the educated and literate people in the world at that time came from the clergy, the Church had authority over the uneducated “common man.” Now, by disseminating thousands of copies of identical religious texts, with reading instruction limited to the Bible, the Church believed it could ensure greater religious conformity and obedience among those people. It realized too late, however, that the invention would actually irreparably undermine its strength by vastly increasing literacy, paving the way for the Reformation and the European Renaissance.

The printing press also had a large impact on the social order by changing the nature of reading within society. Print gave a broader range of readers access to accumulated knowledge, and it allowed later generations to build directly on the intellectual achievements of earlier ones without shifting the verbal language in the process. Acton, in his lecture On the Study of History (1895), gave “assurance that the work of the Renaissance would last, that what was written would be accessible to all, that such an occultation of knowledge and ideas as had depressed the Middle Ages would never recur, that not an idea would be lost.”[2]

With the availability of print material and the subsequent rise in literacy, the nature of reading changed in many ways:

- Critical reading: Once texts became accessible to the general population, people then had the option of forming their own opinions about the works. They could also interpret those works creatively, often in different ways than the author intended.

- Dangerous Reading: At first, reading was seen as a dangerous activity, rebellious and unsociable in nature. This was especially true in the case of women. Reading could stir up dangerous emotions, and women, more so than men, it was believed, were prone to emotional hysteria. As such, they were often excluded from reading and writing instruction.

- Extensive Reading: With more material becoming available on a wide array of topics, people could read extensively and educate themselves in many different areas.

With the advent of the new printing techniques, the occupational structure of Western Europe changed as well. Printers emerged as a new group of artisans for whom literacy was essential; scribes became less needed; and the new jobs of editors and proofreaders, booksellers, and librarians arose.

Printing also made an impact on the educational system. Before the Gutenberg press, there were few books, and most material was written in Latin; after, the number of books increased, and so, too, did the number of languages used. Latin remained an international language until the eighteenth century, but other options were available. And textbooks started to be printed with different levels of difficulty, instead of just as a singular introductory work.

At the same time, universities began establishing accompanying libraries. “Cambridge made the chaplain responsible for the library in the fifteenth century but this position was abolished in 1570; in 1577, it established the new office of “university librarian.” As libraries accumulated more books, they began to run out of room. This issue was solved, however, by a man named Merton (1589) who decided books should be stacked horizontally on shelves.[3]

What are some areas that you see being influenced by the expansion of books and literacy? Please leave us your thoughts in the comments section below.

Next up: The Origins and Development of English, part 1

Citations:

[1] Haley, Allan. (nd). “Gutenberg’s Invention.” Retrieved from https://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fontology/level-4/influential-personalities/gutenbergs-invention

[2] Buringh, Eltjo, and van Zanden, Jan Luiten. (2009) “Charting the ‘Rise of the West’: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 69, No. 2, pp. 409–445 (417, table 2).

[3] Einstein, Elizabeth in Briggs, Asa, and Burke, Peter. (2002). “A Social History of the Media: from Gutenberg to the Internet.” Polity, Cambridge, p. 21.

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

2 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 16: Printing and its Effect on the World (Part 3 of 3)”