[Editor’s note: This is the twenty-fourth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

All of the languages we’ve discussed in this series up to this point, and especially the writing systems, have been naturally occurring. That is, all of them have developed over long periods of time to meet a given society’s needs for stable communication. There are, however, some languages that have been artificially constructed by a single individual or by a small group – these are referred to as “featural scripts,” a term coined by linguist Geoffrey Sampson. Some featural scripts can be found in national writing systems, such as Korean Han’gŭl and the Canadian Inuktitut syllabary. Some can be found in the office environment in various forms of shorthand. And many have been designed especially by science fiction and fantasy writers to lend their created worlds a richer culture – of these, J.R.R. Tolkien’s alphabetic Tengwar and runic Certar, from his “Lord of the Rings” series, are perhaps the best known.

Despite any superficial differences, all featural writing systems reveal their intentional design in everything from the way they’re structured (the arrangement of the signs into grids) to the relationships between each sign’s form and its pronunciation (the signs are not pictorial, abstract, or arbitrary). These are precisely the features that natural scripts don’t show. In a featural writing system, the shapes of the symbols often encode the features of the phonemes they represent.[1]

Many featural scripts are organized based on the way sounds are made in the human mouth. Take, as an example, the sounds represented by the letters “p” and “b.” They’re both made by pressing the lips together, so linguists call them “bilabial.” Air pressure builds up behind the lips and is then released, so we refer to the letters as “plosives.” In addition, we vibrate our vocal cords to make the sound /b/” and we don’t for /p/;” the difference between the two is called “voicing.” “B,” therefore, is a voiced bilabial plosive, and “p” is a voiceless one. In a featural script, these letters would be grouped together on a grid to indicate the language’s plosive sounds, while they are not so organized in naturally occurring scripts. In addition, formal features like sign shape, orientation, and the addition of diacritical marks all reveal phonetic connections between featural signs.[1]

Featural scripts can affect how entire nations read – the world’s best-known featural script is Korean Han’gŭl. Initially, the Koreans adopted the Chinese script, which they used for over 1,000 years. In 1443, though, King Sejong produced a brand-new featural alphabet that became Han’gŭl, the Korean term for “great script.” One reason was the Chinese characters were a complex and cumbersome way to write Korean, as Korean was very different from Mandarin Chinese. Another was that these characters took a long time to master. Still another was they were always the domain of privileged aristocrats as a result of their difficulty. Han’gŭl, on the other hand, was designed for everyone to use. As King Sejong himself noted, “A wise man can learn [Han’gŭl] before the morning is over; a stupid man within the space of ten days.” Like Japanese hiragana, Han’gŭl was quickly adopted by the common people, and it was the only script used by women. Indeed, it eventually proved so effective the government banned its use in 1505–1506 – the royalty didn’t want the masses to become too literate.[1]

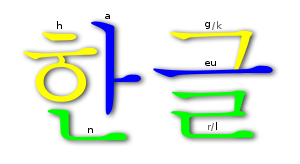

The alphabet consists of 14 consonants and 10 vowels, with the letters grouped into syllabic blocks both vertically and horizontally. The non-linear representation is a holdover from the shape of Chinese characters. In addition, until the 1980s, Korean was usually written from right to left in vertical columns, like the Chinese, though today, the majority of Han’gŭl texts are written from left to right in horizontal lines.

The name Han’gŭl, whose phonemic signs are grouped into blocks

Another example of Han’gŭl’s linearity is seen in the Korean word for “honeybee” (kkulbeol); it is written 꿀벌 (phonemes grouped into blocks), and not ㄲㅜㄹㅂㅓㄹ (phonemes written linearly). As Han’gŭl combines the features of both alphabetic and syllabic writing systems, some linguists have described it as an “alphabetic syllabary.”[2] Some linguists consider it among the most phonologically faithful writing systems in use today, with an interesting feature being that the shapes of its consonants seem to mimic the shapes of the speaker’s mouth as he pronounces each consonant.[3]

As with attempted script reforms in both China and Japan, there has always been some resistance to using Han’gŭl, but by the 19th century it had been adopted as an official script. Today, Korean is still written in a mixed script that uses Chinese characters for the large amount of Chinese loanwords, as well as Han’gŭl for native words. North Koreans write exclusively in Han’gŭl, and South Koreans are slowly heading in the same direction. These factors make Han’gŭl one of the few featural scripts presently serving as an official, national script.

Next up: Featural Scripts (part 2 of 3)

Citations:

[1] Zender, Marc. (2013). “Writing and Civilization: From Ancient Worlds to Modernity.” The Great Courses Lecture DT2241.

[2] Taylor, Insup (1980). “The Korean writing system: An alphabet? A syllabary? a logography?”. Processing of Visible Language. Boston, Mass.: Springer: 67–82. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-1068-6_5. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

and

Pae, Hye K. (1 January 2011). “Is Korean a syllabic alphabet or an alphabetic syllabary”. Writing Systems Research. 3 (2): 103–115. doi:10.1093/wsr/wsr002. ISSN 1758-6801. Retrieved 17 October 2017, both as referenced at revolvy.com, https://www.revolvy.com/page/Hangul

[3] Cock, Joe (2016-06-28). “A linguist explains why Korean is the best written language.” Business Insider. Retrieved 2017-12-02, as referenced at revolvy.com, https://www.revolvy.com/page/Hangul

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 16 (Printing, Part 3), click here.

To read Part 17 (Origins of English, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 18 (Origins of English, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 19 (Origins of English part 3), click here.

To read Part 20 (Origins of English, Part 4), click here.

To read Part 21 (Printing and the Digital Age), click here.

To read Part 22 (Music’s Later Developments), click here.