[Editor’s note: This is the twenty-sixth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

[The blog staff would like to acknowledge the generous assistance of Dr. Marc Okrand in developing the content of this post.]

The featural scripts we’ve discussed so far in this series have all served a defined purpose – a national writing system (Han’gŭl), a fictional communication system (Tengwar), and a universal language for peace (Esperanto). There is another language and its associated script, though, that bears discussion, if only for its unusual place in global society – Klingon.

Klingon is the language spoken by the humanoid warrior race in the Star Trek films and TV series. In the 1984 film, Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, there were several scenes with extensive Klingon dialogue. Director Leonard Nimoy and writer-producer Harve Bennett wanted the Klingons to speak a real-sounding language rather than gibberish, so they hired linguist Dr. Marc Okrand to create such a language, which he termed “tlhIngan Hol.”

Dr. Okrand had only a few “true” sounds to work with, which came from Klingon names and from occasional words used in the series’ episodes and films, so he basically had to start from scratch. He did not base Klingon on any one particular language, but instead he drew on his knowledge of how human languages work. Paramount Studios wanted the new language to be gutteral and harsh, and Okrand wanted it to be unusual, so he combined sounds in ways not typically found in other languages (e.g. a retroflex D and a dental t, but no retroflex T or dental d). All the sounds of the resulting language (and most of the grammar) occur individually in existing Terran languages and could therefore be spoken by human actors, but no single language uses the entire collection he produced, so it would be unique.[1]

But what about Klingon writing? When Star Trek: The Motion Picture was released in 1979, the Astra Image Corporation designed letters to represent the language’s written form. It based those letters on the few symbols created by set designer Matt Jefferies that appear on the film’s Klingon battlecruiser, as well as incorporated features of the angular Tibetan script to suggest the Klingons’ love of bladed weapons. However, the Klingon glyphs in this and other Star Trek films and TV series were used randomly – for effect, not meaning.[2]

According to Okrand, who was not involved in the creation of the written form, “Even after the spoken language was developed (for Star Trek III), there was no attempt ever made to match the written with the spoken, and no one worried about whether the system was an alphabet, a syllabary, or something else. The Klingon Dictionary appeared in 1985, and shortly after that someone took the Astra characters, modified them slightly, and added more so there was a total of 26 characters, each one corresponding to a spoken Klingon sound, so it’s an alphabet. (The fact that there are 26 sounds in Klingon and 26 letters in the English alphabet is a total coincidence or accident.) This set was used by fans of the language and also for some licensed products (the Klingon version of Monopoly, for example, and some books and some other things), but the films and TV shows continued to use the randomly displayed Astra set. (Whoever expanded the character set also developed 10 characters for numbers 0-9). Various fonts have been developed.”[3] Okrand has designated this form as pIqaD.

[Editor’s note: This alphabet and numerical characters were originally leaked to fandom by an unnamed and unknown source at Paramount Studios.]

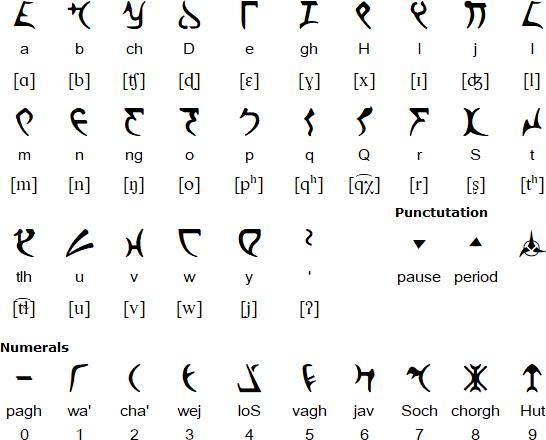

The pIqaD alphabet and numerals, with pronunciation

“All of this changed for Star Trek: Discovery,” Okrand notes. “This new show uses the 26-character set, and they use them to write the spoken language. (That is, for this show, anything written in Klingon really means something, in contrast to earlier movies/TV shows when it was just artwork.) They developed a new font for Discovery, but it’s the 26-character set.”[3]

Klingon script is written in horizontal lines moving from left to right, top to bottom, just as in English. It is written with minimal punctuation (see image above), and the triangular punctuation marks have been accepted into the common usage of pIqaD. Most Klingon users write with a Romanized version of Klingon sounds, however, but this orthographic system (which is also used in the Klingon Dictionary) uses both capital and lowercase letters quite differently from English. Mostly, capital letters are used to help remind you that a letter sounds different in Klingon than it does in English. Correct capitalization is also important (i.e., do not capitalize the first letter of a Klingon sentence, and note that q and Q represent completely different sounds in Klingon), since otherwise it’s hard for people used to the language to read it. This is also true of the apostrophe mark; in Klingon it’s a full-fledged letter. pIqaD, on the other hand, uses only a single case.

How can you tell pIqaD is a featural script? According to Okrand: “For example, in the Romanized version, I use a capital D and an apostrophe. In the Klingon system, the character representing D looks a lot like D, and the character representing the apostrophe [which was not part of the Astra set] looks a lot like an apostrophe. (It was clearly added when the system was modified to match up with my transcription.)”[3]

A standardized, constructed alphabet did emerge with the creation of the Klingon Language Institute (KLI) in 1992, and you can use the Bing translate program for any Klingon text you want to write or decipher, though you need to be careful, as the program is still developing, and it can get “creative” with translations. There are a couple thousand semi-fluent speakers and even more somewhat conversant in the tongue, and the language is growing. The KLI has produced Klingon versions of two Shakespeare plays: “Hamlet” and “Much Ado about Nothing (paghmo’ tIn mIS);” its journal, HolQeD (Klingon for linguistics), contains articles on Klingon linguistics, language, and culture; it publishes jatmey (“scattered tongues”), a magazine featuring poetry and fiction in and about Klingon; and it runs an annual qep’a (“great meeting”). And with the rise of the internet, the language, which is most commonly written with the Latin alphabet, has managed to reach mainstream consciousness, giving the script a unique place in modern society.

Want to hear how Klingon actually sounds? Take a look at this clip from the KLI’s version of “Hamlet”: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CiRMGYQfXrs&t=62s

Next up: The Future of Writing, part 1

Citations:

[1] qurgh. (April 24, 2017.) “Sounds of Klingon.” The Klingon Language Institute. Retrieved from https://www.kli.org/about-klingon/sounds-of-klingon/

[2] Ager, Simon. (2019). “Klingon (tlhIngan Hol).” Omniglot.com. Retrieved from https://www.omniglot.com/conscripts/klingon.htm

[3] Okrand, Dr. Marc. (January 1–8, 2019). IM conversations about Klingon language development.

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 16 (Printing, Part 3), click here.

To read Part 17 (Origins of English, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 18 (Origins of English, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 19 (Origins of English part 3), click here.

To read Part 20 (Origins of English, Part 4), click here.

To read Part 21 (Printing and the Digital Age), click here.

To read Part 22 (Music’s Later Developments), click here.

To read Part 23 (Featural Scripts, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 24 (Featural Scripts, Part 2), click here.

1 thought on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 25: Featural Scripts (part 3 of 3)”