[Editor’s note: This post is part of a continuing series on how writers craft words to express their ideas and to connect with readers.]

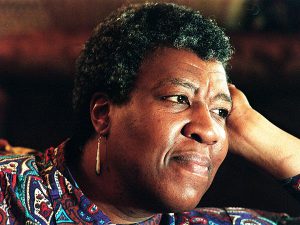

It’s “Jeopardy!” time. The answer is: “She was one of the few female African American science fiction writers, one who won multiple Hugo and Nebula awards for her work, and one who, in 1995, became the first science fiction writer to receive a MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Grant.” The correct question is: “Who is Octavia Butler?”

Born in 1947, Butler grew up in Pasadena, California. Her father died when she was a baby, and she was raised by her grandmother and her mother, who worked as a maid to support the family. Butler grew up in a struggling, racially mixed neighborhood. She was shy and a “daydreamer,” and she was a prodigious reader though later diagnosed as being dyslexic. Her mother would bring home the tattered books her employers threw away. Butler began writing when she was 10, primarily “to escape loneliness and boredom;” at 12, she began a lifelong interest in science fiction. “I was writing my own little stories and when I was 12, I was watching a bad science fiction movie called Devil Girl from Mars,” she told the journal Black Scholar, “and decided that I could write a better story than that. And I turned off the TV and proceeded to try, and I’ve been writing science fiction ever since.”

“When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read,” Butler told The New York Times in 2000. “The only black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway. I wrote myself in, since I’m me and I’m here and I’m writing.”

Butler obtained as associate’s degree in 1968, but she credits two writing workshops for giving her “the most valuable help I received with my writing”:

1. 1969–1970: The Open Door Workshop of the Screenwriters’ Guild of America, West, a program “designed to mentor Latino and African-American writers.” Through Open Door she met science fiction grandmaster Harlan Ellison.

2. 1970: The Clarion Science Fiction Writers Workshop (introduced to her by Ellison), where she first met writer and publisher Samuel R. Delany.

Butler wrote a dozen novels, starting in 1976 with “Patternmaster,” which was to become the fifth chapter in her “Patternist” series. The books are set in periods that range from the historical past to the distant future, and they’re known for their economy of language as well as for their strong, believable protagonists, many of them black women. Butler also wrote short stories, most notably “Speech Sounds,” which won her a Hugo, and “Bloodchild,” which won both a Hugo and a Nebula Award for Best Novelette; both appear in 1995’s “Bloodchild and Other Stories.”

One of Butler’s best-known novels is “Kindred,” published in 1979. It tells the story of a modern-day black woman who travels back in time to the antebellum South so she can save the life of a white, slaveholding ancestor, an act which ultimately saves her own life. The book is frequently assigned in black-studies courses, and it was rooted in her mother’s experience as a maid.

“I didn’t like seeing her go through back doors,” she told Publishers Weekly. “If my mother hadn’t put up with all those humiliations, I wouldn’t have eaten very well or lived very comfortably. So I wanted to write a novel that would make others feel the history: the pain and fear that black people have had to live through in order to endure.”

Ultimately, Butler’s focus on disenfranchised characters serves to illustrate both how minorities have been exploited throughout history and how the resolve of a single, exploited individual can bring critical change to the world they inhabit. Regardless of the topic and the protagonist she chose, Butler always wanted readers to be genuinely interested in her work and the story she provided; however, she also felt that people wouldn’t read her work because it was labeled “science fiction.” As a result, she resisted being branded a “genre” writer, instead suggesting that she appealed to three loyal audiences: black readers, science-fiction fans, and feminists.

In fact, Butler held strong opinions about many social conditions. “Simple peck-order bullying,” she wrote in her essay “A World without Racism,” “is only the beginning of the kind of hierarchical behavior that can lead to racism, sexism, ethnocentrism, classism, and all the other ‘isms’ that cause so much suffering in the world.” As a result, her stories often focused on the domination of the weak by the strong as a kind of parasitism. A protagonist who embodies difference, diversity, and change rises up to defy and defeat the strong “others,” whether they are aliens, vampires, super-humans, or slave masters.

Butler’s last novel, 2005’s “Fledgling,” told a vampire story within a science fiction context. The author commented that the book was a lark, but it is intimately connected to her other works through its exploration of race, sexuality, and what it means to be a member of a community. In addition, it continues the theme, raised explicitly in Parable of the Sower, that diversity is a biological imperative.

Embrace diversity

Unite–

or be divided,

robbed,

ruled,

killed

By those who see you as prey.

Embrace diversity

Or be destroyed.

—From “Earthseed: The Books of the Living,” Parable of the Sower.

In 2000, Charlie Rose interviewed Butler following the MacArthur Fellowship award. He asked her, “What then is central to what you want to say about race?” Butler’s response was, “Do I want to say something central about race? Aside from, ‘Hey we’re here!’?” The answer speaks to why she became not just a writer, but a science fiction writer. The genre offers worlds of possibilities to explore different themes, and while race is an innate element of her stories, it is part of the narrative, not something she forced upon it.

“We are a naturally hierarchical species,” Butler commented to The New York Times, also in 2000, explaining why her chosen genre is ideal for providing social commentary. “When I say these things in my novels, sure I make up the aliens and all of that, but I don’t make up the essential human character.”

Butler died in 2006 following a fall, at the age of only 58.

Next week: Philippa Gregory