[Editor’s note: This is the eleventh of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

It appears that the Etruscans, who inhabited a region in and around what is now Tuscany, Italy, were the first people in the Italic peninsula to learn to write. They started sometime in the 8th century BCE, adopting the version of the Greek alphabet brought to them by the Euboeans (who inherited it from the Phoenicians) as a starting point. Over the next eight or nine centuries, they changed and refined their script, but it eventually gave way to the Latin alphabet as the people were conquered and assimilated by the Roman Empire.[1]

During the 20th century, there was a pervasive idea that there was some sort of “mystery” about the Etruscan language, but that’s not exactly true. Scholars have had no problem reading what texts have been found, because, as a variant of Ancient Greek, the alphabet is largely legible, and we know how it was pronounced. It’s also relatively easy to follow its variations over time. However, two major problems muddy the waters. First, there appears to be no relationship between the Etruscan language and any other language in the world. Modern linguists have tried to assign it to one of the various linguistic groups within the Mediterranean and Eurasian regions, but the attempt has been mainly futile – it’s an isolate. Without another, known language with a close enough kinship to Etruscan to allow a reliable, comprehensive, and conclusive comparison, there is no way to determine what much of the written script means. And while some have claimed to find similarities in the lesser-used, non-Indo-European languages, the evidence does not yet strongly support it.[2]

Second, there is a very small amount of actual text that has survived to this day, and it is limited in scope. It comes primarily from tombstones – no dictionaries or grammars have been found. That means you’ll get a lot of geneological words, personal titles, and brief dedicatory sentences, but not much more. That’s not really enough to go on to reconstruct an entire language. Without the source material to understand the words and grammatical forms, the Etruscan language remains beyond our current reach.

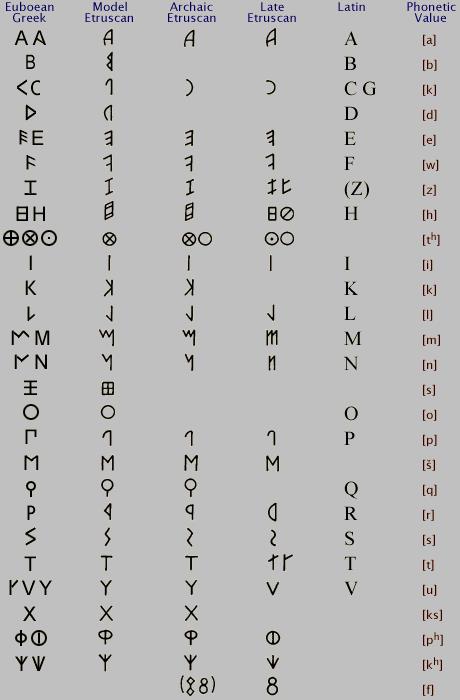

This table represents the various stages the Etruscan alphabet went through over its lifetime. The “Model” alphabet is basically the Greek alphabet inherited from the Euboeans; it was probably not used but was most likely learned as part of a literate person’s training, in much the same way we, today, study Greek or Latin. The “Archaic” alphabet was used between the 8th and 4th centuries BCE, before the Etruscans became part of the Roman Empire. The “Late” version was used from the 4th century BCE to the 1st century CE, a period when the Etruscan language was rapidly being replaced by Latin.[1]

What we do know of the Etruscan language, as we’ve mentioned, we’ve obtained from epigraphic records (inscriptions) in the Tuscan area, dating mostly from around the 7th century BCE to the beginning of the new millennium. All told, we have some 10,000 examples, mainly brief and repetitious epitaphs or dedicatory formulas, votive or owner’s notations on paintings in tombs, and engraved figures on small artifacts such as metal mirrors. There are, however, some remarkable exceptions, and the differences in their origins are critical to understanding something about the Etruscan culture of which we know so little.

The longest single text contains 281 lines (about 1,300 words). It was written on a linen roll that was subsequently cut into strips to use as a mummy wrapping in Egypt. A private collector bought the mummy in the 19th century and kept it, unseen, in a private collection. Following his death, it made its way to the National Museum at Zagreb in Yugoslavia, where scholars discovered the ancient writing. It contains both a calendar and instructions for a sacrifice, sufficient information to give us some idea of Etruscan religious literature, but no idea how the information made its way to Africa in the first place. A clay tablet found at Capua, in southern Italy, contains about 250 words; a boundary stone slab from Perugia has two adjacent sides engraved with a 46-line (some 125 words) inscription. The first is a religious text, the second is noteworthy for its legal content. But perhaps the most important finds were inscribed gold plaques found at the site of the ancient sanctuary of Pyrgi, the port city of Caere. These provide two texts of about 40 words each, one in Etruscan and the other in Phoenician, of identical content. The equivalent of a bilingual inscription, these bitexts provide substantial data for the deciphering of Etruscan by way of a known language – Phoenician.[2][3]

By the time the Roman Empire had risen in the 1st century CE, Etruscan was essentially a dead language, though priests and scholars continued to study it. The emperor Claudius (DOD 54 CE) wrote a 20-book history of the Etruscans, which was based on sources still available in his day, but that history did not survive into the present. The language continued to be used in a religious context for a few centuries more. The final preserved record relates to the invasion of Rome by Alaric, chief of the Visigoths, in 410 CE; Etruscan priests were summoned at that time to conjure lightning against the barbarians.[2]

Next up: Meroïtic script

Citations:

[1] (na.) (2012.) “Etruscan.” AncientScripts.com. Retrieved from http://www.ancientscripts.com/etruscan.html

[2] de Grummond, Nancy Thomson. (nd) “Ancient Italic People.” Brittanica.com. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/ancient-Italic-people#ref249576

[3] Fowler, Murray. (nd.) Etruscan language. Britannica.com. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Etruscan-language

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

3 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 10: Etruscan, an Undecipherable Language”