[Editor’s note: This is the eighteenth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

English uses an alphabetic writing system based on Latin. Though Latin was spoken in England during Roman rule (43–410 CE), the written language was brought to the Anglo-Saxon island by Christian missionaries during the 600s. Before this time, an earlier Germanic writing system known as runes was used (see post on runes here). It was also alphabetic and was derived from the same source as the Latin alphabet, though it was used for more limited purposes (i.e. incantations, curses, and a few poems). The oldest known piece of written English is the Undley Bracteate, a gold medallion with a runic inscription that reads “this she-wolf is a reward to my kinsman.”[1]

As we’ve seen in previous posts, alphabetic writing systems are based on the principle of using written characters to represent spoken sound segments, specifically those at the level of consonants and vowels; ideally there should one written character for each sound segment. Other kinds of writing systems are based on written representations of different linguistic units such as syllables, words, or a combination of these.[2]

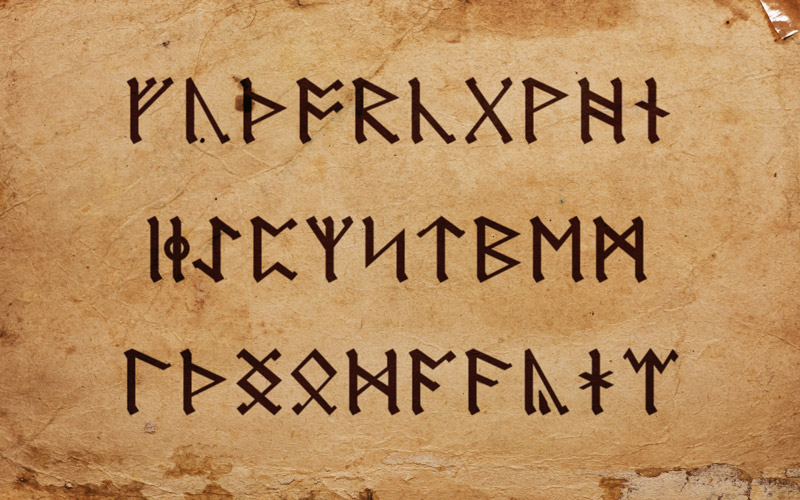

The Old English alphabet, which combined Latin and runes, looked like this:

This runic alphabet is also sometimes called the futhorc, which is derived from the pronunciation of the first six letters. Experts are divided regarding the path futhorc took to reach the British Isles. Some believe it was brought by immigrants from Frisia (the northern Netherlands), while others think it came from Scandinavia and moved to Frisia at a later time.[1]

The Roman alphabet was constructed from a language with a very different phonological system than English; as a result, it was never ideal for writing English even in its original use representing the Anglo-Saxon. The first monks who wrote English using the Roman alphabet system discovered they had to add new characters to handle the extra sounds. For example, they created a ligature of “a” and “e” to represent the front low vowel /æ/ of Anglo-Saxon, forming a single written character called “ash.” They also added a few runic characters to the alphabet to represent consonant sounds not found in either the Latin or its Romance descendants, such as the fricatives thorn þ, eth ð, and yogh ȝ. Later on, these runic characters were replaced with digraphs, two-letter symbols such as th, sh, and gh, where the letters are used as a compound to indicate single sounds.

The norms for writing words consistently using a given alphabetic character set are collectively called an orthography. A specific orthography was never used as an absolute in Anglo-Saxon because this was an entirely new system, and norms for writing words in a consistent way takes place over a relatively long time period. It’s not easy for writers to remember a single orthographic representation, called a spelling, for a word unless a perfect one-to-one correspondence between phonemes and graphemes exists. This correspondence is what’s required for standardization, but it’s an ideal rarely achieved with alphabetic systems. Most writers prefer using written forms they’ve seen before for specific words, even if no good match exists between the written characters and the sounds they represent.[2]

One might think that simply pronouncing a word based on the graphemes present would be easy enough to allow a reader to orally match the written form; however, it turns out such processing is not a simple cognitive task. Analyzing the sound string down to the level of component sounds – phonemic analysis – is neither obvious nor a natural process for humans; it needs to be taught intensively before it can be done automatically, and it takes a lot of practice to get to that stage. This is one major reason why cultures with alphabetic writing stress early acquisition of literacy. Syllables appear to be a more natural unit for humans to perceive and therefore to code (write) and to decode (read) by means of written marks. Humans also decode faster the more familiar they are with the specific written forms. [See our post on “Humans are Hard-Wired for Speech but not for Reading and Writing” here.] As most manuscripts at that time were apparently read aloud, the process was slow enough to allow for relatively fluent decoding.

Whatever consistency might have been present at the beginning of using the Roman alphabet for representing Anglo-Saxon lessened quickly. The novelty of the alphabetic system as a technology, the lack of fixed norms for written representations, and the changes over time of the language were all forces that led to greater divergence of the written forms from the spoken string. This was further compounded by variations in regional dialects.

Monks copied large numbers of manuscripts using quill pens, ink, and either prepared sheepskins (parchment) or the more expensive and high quality calfskins (vellum), and the physical technology of this system remained pretty much the same for 800 years. While some norms arose for spelling, the sounds of the oral language were changing faster. As usual with written languages, the norms for writing lagged behind those for pronunciation, aiding the divergence of the written form from the spoken.

Next up: Origins and Development of English, Part 2

Citations:

[1] Ayancan, George Millo. (2018). “Old English Writing: A History of the Old English Alphabet.” Retrieved from https://www.fluentin3months.com/old-english-writing/

[2] Kemmer, Suzanne. (2009). “The History of English.” Rice University. Retrieved from http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~kemmer/Histengl/spelling.html

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 16 (Printing, Part 3), click here.

2 thoughts on “The History of Writing and Reading – Part 17: The Origins and Development of English (Part 1 of 4)”