[Editor’s note: This is the twenty-third of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

In Part 13 of this series, we discussed the earliest examples of musical notation and the relationship of written music to written text. Over the centuries since the first pieces were set down in stone, many more changes were made to improve and refine the quality of musical codification until we arrived at the system we use today. Here are a few of the milestones along the way.

In about the year 1025, a monk named Guido moved to the Tuscan city of Arezzo; it’s no great surprise, then, that history has dubbed him Guido of Arezzo. While we don’t have much information concerning his biographical details, we do know he was one of many individuals who contributed to Western Europe’s musical expression. He organized pitches into groups called hexachords (sort of like a scale) and pretty much invented solfege (“do-re-mi-fa…”) single-handedly. In addition, he advanced a method for notating those concepts more accurately on the page.[1]

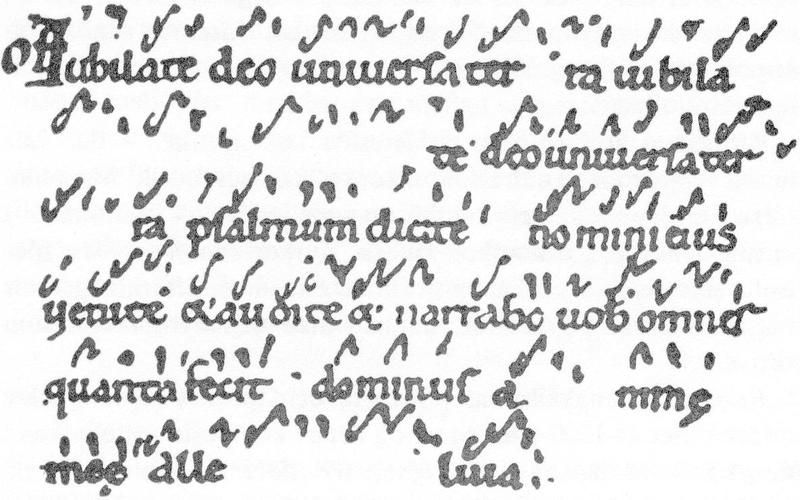

Before Guido’s time, liturgical music was notated by using markers called neumes. If you were learning a chant, for example, you’d have the words written on a piece of parchment. Above the words you’d see neumes – these would slide up or down, or twist or turn. The neumes wouldn’t tell you which specific note to sing; instead, they would indicate the contour of the melody. If a line above a word rose, you would raise the pitch; if it fell, you would lower the pitch.

Text from the chant “Iubilate deo universa terra.” The neumes appear above the words. (Wikimedia Commons)

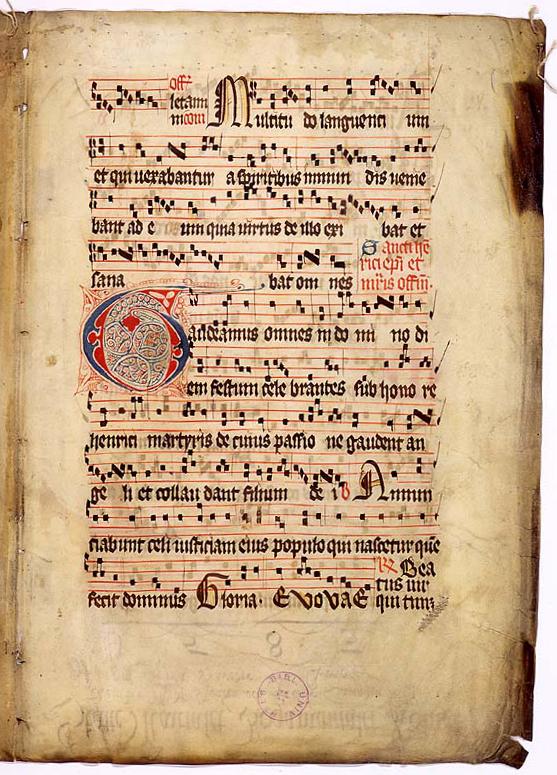

The trouble was, it was an inexact practice, and, in his visits to monasteries, Guido observed that the singers struggled to learn chants in the repertoire. So, he created a notation that would allow someone to learn a piece even if they had never heard the music before: the staff. His staff had four lines, instead of the five we use today, and one of them was marked with a “key indicator” — maybe a C or an F — that indicated its fixed pitch position. Two of those lines would be colored — yellow for C, and red for F. This allowed the young students to “better detect the level of pitch,” or, to put it more simply, to read the music. We should note that smaller staffs and color coding may have been in place before Guido’s time, but it was he who pushed the writing forward.

Neumes on Guido’s new, four-line staff. (Wikimedia Commons)

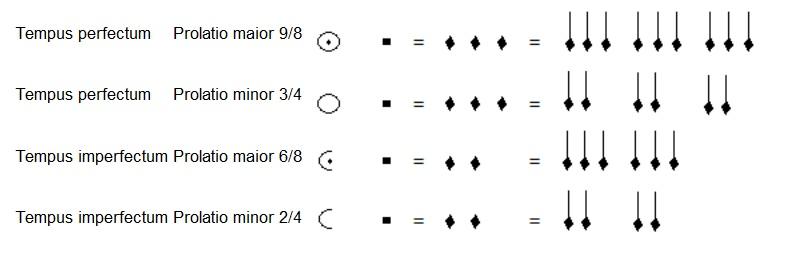

These were great advances, but there was still a problem – how long should each note be held? The answer was mensural notation. Mensural means “related to measuring things,” and that’s exactly what mensural notation did, although it was normally used for secular vocal music, and it appeared on a five-line staff. These symbols are very clearly related to the ones we use today.

Each breve, or note value, could be broken down into semibreves, which could be further divided into proportionately smaller values – a whole note equals two half notes or four eighth notes. Corresponding rests also indicated periods of silence. Take a look at the table below for what these symbols looked like, as well as their modern counterparts.

And mensural signs, which consisted of some combination of circles, half circles, and dots, indicated the relationship of those notes for a piece — sort of like a rudimentary time signature.

As we’ve said, mensural notation was largely used for secular vocal music. However, instrumental music became more prevalent starting around the 17th century. While all types of musicians willingly co-opted the staff and notation of the day, they did find it quite limiting when it came to communicating information about what instruments other than the voice should do. Over time, other individuals added barlines, stylized clefs, dynamic markings, ties, and slurs to the notational repertoire. You can see these marks in the piece below:

The beginning of the cello part for Mendelssohn’s Piano Trio No. 2 in C minor.

(IMSLP)

While each of the notation marks seems relatively simple on its own, together they can form a complex language able to be shared from one person to another. Learning to read this notation takes effort and practice, just like any other written script, but, once learned, it’s something you can transfer from one instrument to another, just like reading books of different genres or subjects.

Next up: Constructed Languages (Featural Scripts), Part 1

Citation:

[1] Bennett, James II. (Jun 15, 2017). How Was Musical Notation Invented? A Brief History. WQXR Blog. Retrieved from https://www.wqxr.org/story/how-was-musical-notation-invented-brief-history/

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 16 (Printing, Part 3), click here.

To read Part 17 (Origins of English, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 18 (Origins of English, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 19 (Origins of English part 3), click here.

To read Part 20 (Origins of English, Part 4), click here.

To read Part 21 (Printing and the Digital Age), click here.