[Editor’s note: This is the twenty-eighth of an ongoing series that examines the rise of writing – and therefore reading – around the world. We will be looking at the major developments and forces that shaped the written languages we use today. Links to all the previous posts are listed at the end of this one.]

We discussed in Part 21 – Printing in the Digital Age – that advances in keyboarding and the rise of eBooks led digital media to at first overtake print book sales before plateauing. While that might seem to be encouraging for lovers of printed material, remember that when all the other new technologies were introduced throughout history, they were used concurrently with the old technologies for great lengths of time – up to 800 or so years. So what is our writing future actually likely to be?

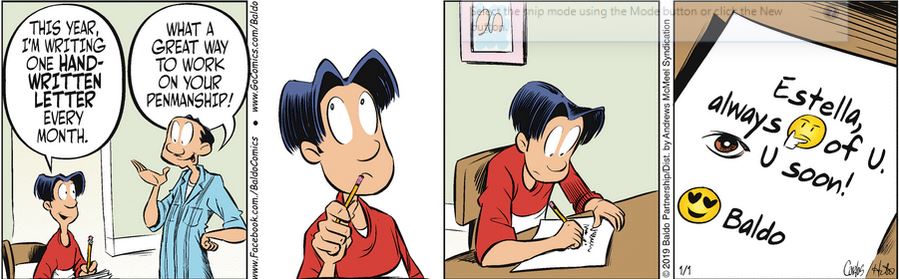

To start with, keyboards and typing are likely to replace handwriting in most instances. Gone are the days of sending handwritten letters and taking notes in class with a pen and paper. Everyone’s go-to now is a phone or a tablet or a computer. We no longer value the art of penmanship, and, in fact, cursive writing instruction has all but ceased in public schools, with keyboarding replacing it. The invention of the keyboard has already altered our writing system in that it has led to the developments of new signs and new spelling conventions. Emoticons, which can be traced to early computing in the 1980s, are a useful addition to the way we write. They supplement both the question mark and the exclamation mark, conveying emotive features of speech that are difficult to capture in written form. The more recent addition of emojis has taken the convention one step farther. While many “purists” decry new texting conventions and associated shorthands as debasements of our “correct” writing system, the truth is that that our writing system has never been fixed in stone. Signs, spelling practices, and words themselves have changed appearance and meaning many times since the invention of the English alphabet – what we are seeing now is just another step along the path of language evolution.

A modern view of penmanship, from the comic strip “Baldo.”

Futurist William Crossman predicts that writing itself will become obsolete by 2050, since by that point computers will be able to intelligently respond to our voices; as a corollary, everyone will be able to communicate with everyone else without ever having to learn to read and write, and illiteracy will become a negligible concern. However, an understanding of the root causes of illiteracy shows that even the demise of writing would probably do little to correct the problem. Literacy is determined by economic, social, and political factors, particularly the crushing poverty, repressive social policies, and lack of political clout for those seeking reform found in many African and Asian countries. Talking computers could never solve the illiteracy problem because neither the technological infrastructure nor the fiscal resources to take advantage of such an innovation exist in the places where the lowest literacy rates exist today.[1]

Anthropologist Dan Sperber agrees with Crossman that the ongoing revolution in information and communication technology might lead to the retirement of writing as an active process; machine transcription of speech might replace our need to physically write down or key in information. However, he is somewhat more hesitant in his view of the scope of the change. Reading, he believes, is here to stay. Even if everything is digitized and stored in a computer, would you want to access material only by having it read to you and not even having the words appear on the screen? Would mothers give up reading to their children so that the computer can do it for them? The mere thought resonates with a “Brave New World” kind of vibe, and it seems more frightening than practical to many people. But I suppose any new technology must seem frightening to a civilization at first.[1] The greatest impact on computer reading, at least for the moment, seems to be the variation in screen and font sizes, as well as the type of font used on a website or in an email or text.

For the moment, speech recognition software still isn’t quite advanced enough for the future both Crossman and Sperber envision, but it’s developing rapidly, and it’s not hard to imagine a near future where a writer might draft all her materials by speaking to a computer. It’s already an integral part of text-to-speech programs used by blind and low vision persons to access digitized information not available in braille. What is unlikely, though, is that the shape of the script produced by computers will change. Whether we access it on hard copy, on display screens, or in retinal readouts, English will most likely continue to be visually represented by the alphabet, which has served us in some form for about the last 4,000 years, and which saw the last major improvement made by the Greeks about 3,000 years ago with the addition of vowels.

The earliest evidence of written text dates back only about 5,000 years – a blip in the timescale of humans as a species – but writing has become an integral part of almost all major civilizations since that time. Its changes have mirrored new technologies and new ways of life, but it has persisted in some form for all that time. To understand where it may be heading, we must look to what has been codified in the writing itself, as it mirrors our history, past and future.

What are your thoughts on the future of reading and writing? Are they an inherent part of our civilization, or are we at a great turning point where they will become obsolete? Leave us your comments in the section below.

Citation:

[1] Zender, Marc. (2013). “Writing and Civilization: From Ancient Worlds to Modernity.” The Great Courses Lecture DT2241.

To read Part 1 (Sumerians), click here.

To read Part 2 (Egyptian hieroglyphs), click here.

To read Part 3A (Indo-European languages part 1), click here.

To read Part 3B (Indo-European languages part 2), click here.

To read Part 4 (Rosetta Stone), click here.

To read Part 5 (Chinese writing), click here.

To read Part 6 (Japanese writing), click here.

To read Part 7 (Olmecs), click here.

To read Part 8 (Mayans), click here.

To read Part 9 (Aztecs/Nahuatl), click here.

To read Part 10 (Etruscans), click here.

To read Part 11 (Meroïtic), click here.

To read Part 12 (Runes and Futhark), click here.

To read Part 13 (Musical Notation), click here.

To read Part 14 (Printing, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 15 (Printing, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 16 (Printing, Part 3), click here.

To read Part 17 (Origins of English, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 18 (Origins of English, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 19 (Origins of English part 3), click here.

To read Part 20 (Origins of English, Part 4), click here.

To read Part 21 (Printing and the Digital Age), click here.

To read Part 22 (Music’s Later Developments), click here.

To read Part 23 (Featural Scripts, Part 1), click here.

To read Part 24 (Featural Scripts, Part 2), click here.

To read Part 25 (Featural Scripts, Part 3), click here.

To read Part 26 (Future of Writing, Part 1), click here.